Designing Traps - Homebrew

Header Art: Dungeon Master’s Guide by Wizards of the Coast

The biggest struggle I face when creating traps is setting the DC to notice it. On one hand, I don’t want my party to find it so I get to watch my Super Original, Top Tier trap go off. On the other hand, it’s not fun for the players if they had no chance in defeating the trap and they just get smashed by a fallen tree in the middle of a temple with no warning or preamble. As the GM, I’m responsible for deciding the DC and I can feel the pressure of cranking it up to ‘protect’ my trap, but also wanting to make it low enough that my players won’t feel like they are just being screwed by me.

Traps are complicated. Not just in their design, but also in their execution. If you make a trap to obvious to your players, than it’s not really a trap. If you make it almost invisible, than you were unfair to your players as you never gave them a chance to defeat it. Unfortunately, I don’t feel as if the Dungeon Master’s Guide (2014) provides enough guidance on traps and their presence in an encounter, in a hallway, or at the table. There are common pitfalls (see what I did there?) when it comes to creating traps, like making the traps too hard for your table to overcome or that can kill a full-hit point, raging barbarian in a single hit.

Traps CAN be fun for the whole table. Not every trap I’ve thrown at my party has even been about hurting them, though one day a character is going to get really hurt when my sphere of annihilation trap finally works. Each trap I placed was based on the party’s skills and abilities, making the party have to work together to solve or avoid it. This post is going to be aimed at talking about traps, their deadliness, as well as provide a few of my own traps I’ve made at the end of it all.

Traps

When I’m talking about traps, I’m talking about situations where the party might suffer a setback, damage, or to ward an area. Traps are specifically different from hazards in that traps are often purposefully designed to thwart other creatures, while hazards are typically naturally forming. Hazards can be improved by creatures, maybe by expanding a canyon or filling a moat with alligators, but there is typically a lack in purposeful damage. Hazards are great at deterrence by just existing, while traps are purposefully made to harm in some way.

The Dos of Trap Design

When creating traps, there should always be a few things floating at the top of your mind. By sticking to this advice, you can ensure that traps are fun for the table, instead of just fun for you. It can be too easy to fall into the trap (I’m so good at these puns!) of making traps that will always succeed, making it so that your players lose agency and ability to overcome them.

On Level. The Dungeon Master’s Guide provides DCs and damage for different traps depending on the party’s level. It’s important to remember what your party can do at their level and how many hit points they have as even a ‘Setback’ trap would be enough to knock out or even kill a level 1 character.

Interesting Threats. A trap is there to provide a break from exploration and to get the players to lean forward in their seats. It is to ramp up the tension in the game. If the trap is just another pitfall trap easily avoided, the trap is boring. Traps should present interesting threats to your party to keep them engaged.

Traps give XP. The Dungeon Master’s Guide unfortunately doesn’t advise you to give XP for interacting traps, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t. When my party overcomes a trap, meaning they either survived it when it was set off or they were able to thwart it, they get experience points. The amount is based on the chart in Chapter 3 Creating a Combat Encounter, I pick a trip difficulty of either Easy, Medium, Hard, or Deadly - and award the players the corresponding amount based on their level. I’ll even award additional XP, and make sure I specifically tell the table this, for coming up with fun or weird ways of defeating traps.

There is Always a Way. No matter what type of trap you are building, there should always be a way for the party to defeat it or circumvent it. It could be costing time, resources, or similar, but there should be at least one way for the party to overcome the trap, or else you are just punishing them and they can’t do anything about it.

On Theme. Traps should not feel out of place in their setting. If you are deep underground, then there probably aren’t going to be massive logs ready to smash through your players. This also goes for if you are standing in the main foyer of the king’s castle, unless there is a very good reason for it, it wouldn’t make sense theme-wise for there to be a trap in such a well-traveled place.

The Don’ts of Trap Design

Just as there are things you should follow in trap design, there are also pitfalls (boom!) you can stumble into. Remember, this is not an opportunity for you to ‘defeat’ your players. Traps are not a GM vs Player mindset, but rather opportunities to introduce very painful puzzles and breathe life into an old tomb. They provide a palate cleanser from constant fights or exploration, allowing your players to try skills and ideas that won’t work in a combat encounter.

You’re Dead. A trap designed to just kill a character outright, even when they are at full hit points can be enticing, but it ultimately makes a player feel useless. They might have gotten a single save or you rolled a single die, and that was all that separated them from permanently losing a beloved character. Traps are not character killers unless players are given ample opportunities to avoid the trap, just like in a combat encounter. You wouldn’t throw a monster that kills a character in a single hit, but rather through multiple hits across several rounds that allow the character to fight back or to flee if need be.

Punishing. If your players have built characters to be the most perceptive that they can be or to be very good at defeating traps, and then you specifically make all your traps impossible for them to find or to defeat, you are making it so that their character choices were meaningless. This destroys their player agency, making it so that no matter what they do, they can never succeed. This is a recipe for disaster and draining all of the fun out of the game.

Less is More. By creating fewer traps, but rather making them more interesting, you ensure that traps are not groan-inducing at the table. No one wants to watch the rogue spend half an hour rolling the same check over and over to defeat yet another pitfall trap. In addition, if you keep traps sparse, it means that your players aren’t going to be slowing down the game as they check every hallway, door, statue, or gold coin they come across, paranoid that they are about to get hit.

But Why? Traps should have purpose and meaning, few people are going through the expense and effort of trapping a random broom closet unless they are trying to kill their servants. Traps need to have a reason for their placement, otherwise, it can feel like lazy dungeon design and a lackluster way of draining party resources.

Specifically Countering Plans. If your traps are designed to get around the preparations of your players, when there isn’t a very good reason why the traps would be designed in such a way, then you are specifically telling the players that no matter what they do, it is meaningless. I’ve created traps after learning that my party has prepared something specific - but rather than countering what they had prepared for, the trap instead was countered by their preparations. Not only does it make the players feel good for thinking ahead, but it also gives me a chance to further push the theme of whatever place they are currently dungeon diving in.

Perception vs. Investigation

My general rule of thumb is that a perception check will help you notice that something seems suspicious about the area ahead of you, and it requires an investigation check to determine what it is.

Like if the players come across a door, I’ll either use their passive perception if they aren’t looking for traps or have them roll perception checks if they are actively looking for traps. On a success, I then inform them that something about the door handle looks wrong. If they want to figure out what is wrong, they then must succeed on an investigation check, where they can then realize that the door handle has a small wire wrapped around it, and it leads to behind the door - an obvious sign of a trap.

Each skill has a specific use, with their primary ability score helping to determine when you should use that skill. Wisdom (Perception) is about your gut and realize that something isn’t right or feels off. Intelligence (Investigation) is using your head and applying logic to the situation, figuring out what it all means.

Monster Team-Up

By adding in monsters to a trap, especially one with multiple stages to it, you can force the party to split their attention. One character might be focused on stopping the sliding walls to smoosh them together, while the other three fight the ghost or specter that keeps moving in and out of the walls, attacking and draining their essence.

In such situations, trap damage should not be very severe or the monster should not be a very severe fight, simply because that party will not be able to keep up with both. The monsters or the trap should be easier to overcome, giving the party a chance to survive the ordeal.

Traps

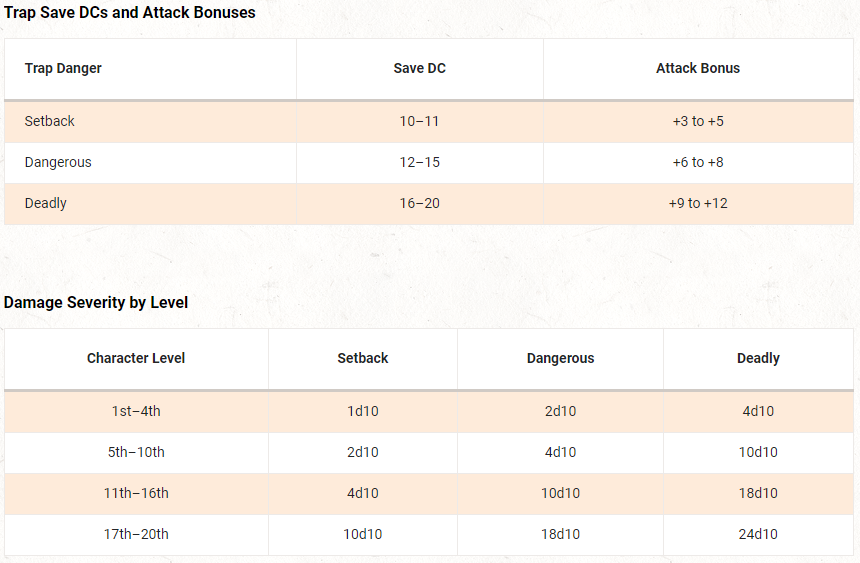

Now that we’ve gone over the Dos and Don’ts of trap design, here are a few traps that I’ve used throughout my games. I have not added in specific DCs or damage, but rather have key terms in place. Those key terms are directly related to the charts found in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, which are included here for ease of reference. This way you can easily see how deadly the traps are supposed to be, but also so that you can add in your own numbers in case you want something easier, deadlier, or something in between.

When deciding how difficult or dangerous a trap is, remember that everything should be a give and take. If you make a trap ULTRA-DEADLY, then the DC to spot the trap should be fairly low. If you make a trap be very hard to spot, then disabling the trap should be easy for someone who knows where the trap is. There should be a give and take, just like monsters have a give and take. There aren’t monsters that deal massive damage, have the most hit points, have the highest AC, and the best attack roll this side of a kobold cavern. There is a balance where if they have few hit points, they may have a higher AC, and their damage might be very low but they have a big attack bonus to make up for it.

Dungeon Master’s Guide, 2014 WotC

Dual-Sided Pits

Magic Trap

Along a thin hallway are two pits, one is dug into the bottom of the hallway, the other into the ceiling. They often appear like a hallway a 10-foot wide hallway. It is very easy to jump the gap so long as a creature has a Strength score of 10 or higher.

When the first creature jumps across the pits, the trap is armed. A character that succeeds on a DC dangerous Intelligence (Arcana) check can feel that there is now magic active in the two pits, or a spell or other effect that can sense the presence of magic, such as detect magic, reveals a transmutation aura in the two pits. The two pits are linked together with a reverse gravity spell.

The trap activates when a second creature moves across the gap and they must succeed on a DC dangerous Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics). On a failed check, they immediately fall up the pit as the reverse gravity spell changes gravity, throwing off their jump and they fall up the top pit, taking falling damage when they hit the top. After six seconds, the spell ends and any creatures at the top of the pit then fall to the bottom of the bottom pit, taking falling damage when they hit the bottom. While they are falling, they are given a chance to make a DC dangerous Strength (Athletics) or Dexterity (Acrobatics) to grab the ledge in between the two pits and stop themselves from falling.

The trap continues every round to activate the reverse gravity spell cast on it, causing all creatures to fall up to the top pit, and then the next round to turn off, causing all creatures to fall to the bottom pit. This lasts for 1 minute. The distance of the two pits is based on the severity of the trap, as a creature takes 1d6 for every 10 feet they fall. For low level, the trap may only be a total of 20 feet, while for higher levels, it could be a total of 100 feet.

A creature with a climb or fly speed has advantage on the initial check to move in between the pit or using ropes anchored on each side. A successful dispel magic (DC setback) cast on the pits destroys the trap, though the pits still remain.

Timed Trap

Mechanical Trap

This trap features two separate pieces, a pressure plate in one room and a sliding door in another. When the pressure plate is pressed, the sliding door is lifted up 10-feet. It then slowly begins descending down at a rate of 1-foot per round. After 1 minute, the trap is sealed again. The objective of this trap is to depress the pressure plate and then run as fast as possible to the slowly descending wall, and make it under before it completely seals.

The pressure plate is obvious to spot and requires no check to see it. A creature that weighs more than 100 pounds can step on the pressure plate, and then can succeed on a DC setback Wisdom (Perception) check to hear grinding stone in the distance. Its not until later that they find a stone wall with scratch marks going up and down its face that they can then make a DC setback Intelligence (Investigation) check to realize that the stone block moves up and down, and that it is the pressure plate that activates it. They can also realize that a normal creature, dashing every time on their turn, would be unable to cross the expanse in time as the door and pressure plate are more than 600 feet from each other.

This is a puzzle for your players to figure out how to succeed against the trap. The distance between the pressure plate and the door can be increased to make it harder on them, just as the thickness of the wall can make it very dangerous. If the wall is 3-feet up, it is difficult terrain to move under it. If the wall is 1-foot up, it takes 15 feet of movement for every 5 feet they move. The sliding wall could be only 1-foot thick or 10-feet thick to make it even harder to move under. It is assumed that only one character has to sprint the distance as the rest can easily move under the raised wall while the other character must be activating the trap.

The wall descends on initiative count 15. A creature can attempt to hold the door in place by succeeding on a DC deadly Strength (Athletics) check to hold the wall up. On each success, this delays the wall’s descent by one round, so that the sprinting character has an extra round to make it. The wall can also be destroyed, it has AC 15, and 30 hit points per inch of thickness. The wall applies 100 pounds of force per foot of thickness, meaning that if it is 5-feet thick, it pushes down with 500 pounds of force.

A creature that is caught under the falling wall, and is within 5 feet of entering or leaving the wall, can use their reaction to succeed on a DC dangerous Dexterity saving throw, pulling themselves out just in time before the wall crushes them. On a failed save, a character must succeed on a DC dangerous Constitution saving throw, taking dangerous damage. They can use an action on their turn to attempt a DC deadly Strength saving throw or Strength (Athletics) check to push the wall up slightly and move 5-feet in a direction of their choice. At the end of each of their turns, they must repeat the Constitution saving throw. If this reduces a creature to 0, they immediately die and their body and equipment are completely flattened.

Trapped Stairs

Mechanical Trap

This trap is set up on a set of stairs and requires that two pressure plates are stepped on to activate, one after the other. There is a pressure plate at the top of the stairs, which arms the trap, and one at the bottom of the stairs, which activates the trap. Once activated, the stairs could collapse into a slide, funneling the triggering creatures into a pit, spikes erupt into the staircase, acid pours from the ceiling, or any other effect.

At the top and bottom of the stairs is a pressure plate. The DC to spot the pressure plate is setback. A character can successfully disable a pressure plate by succeeding on a DC setback Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools) check or a DC setback+2 Strength (Athletics) check to shove a piton or similar item under the pressure plate. On a failed check, they don’t realize that the pressure plate can still be activated.

If the trap is triggered, everyone in the stairwell must succeed on a DC dangerous Dexterity saving throw. Since this stairway can have a variety of different effects, this might be to avoid taking damage from spikes that shoot into the hallway or to avoid sliding down the staircase-turned-slide. On a success, a creature takes half damage or grabs into the railing or some other protruding object.

The trap resets after 1 minute. This trap is most often built when a snarecrafter knows that there is likely to be a large group of people walking down the stairs at a time.

Like what we are doing here?

Support us on Patreon!

You’ll get early access to deep dives, our Homebrew Hoard, monster stat blocks and more!

Follow us on Twitter to keep up to date on everything we talk about!