You're Mapping Your Dungeon Wrong

Since the conception of Dungeons & Dragons, maps of dungeons have been a hallmark. While the original version of the game put a greater onus on the players to make their own map of the dungeon, and hopefully the players were mapping correctly or they were going to get very lost, with virtual tabletops and adventure modules, more and more beautiful maps have begun to appear.

While many may have very strong opinions about Mike Schley's dungeon maps vs Dyson Logos’ dungeon maps, we can all agree that they create very cool dungeon maps. But they have a problem with their complexity. Who wants to think about making hallways and rooms and doodling flourishes along the outside of the dungeon when you have four other nerds at the table telling you about how they kick down every door they can see in a hallway at once, heedless of traps, monsters, and something about ‘artistic talent’.

But I’m here to tell you that maybe those dungeon maps are a bit superfluous. Sure, they are nice to have - but they aren’t a requirement. If you are wanting to make your own dungeon map, you don’t need to spend all your time drawing corridors, properly laying out a megadungeon under the town, or figuring out just how many latrines are needed per the number of monsters in the dungeon. Those details, while nice to have for some ‘just-in-case scenarios’, aren’t a requirement for drawing out a dungeon map.

The Dungeon Diagram

I want to tell you about a dungeon you visit where you don’t have corridors drawn out. You don’t have little nit-pick details, random stretches of hallways that encapsulate one side of the map, trying to remember where stairs lead to, or where you put that party of lost goblins. No longer must you shift through dozens of similar-looking rooms that you put in there so you could fill the space up a bit.

Instead, let’s talk about the Dungeon Diagram. This is a simple tool where you simply draw circles (or squares, or triangles, or whatever shape you want), and then connect the shapes with lines. These shapes you draw are the important parts of the dungeon, while the lines are simply passages that the player characters follow along in a narration-style event.

Looking at the example on the right, taken from the mystery adventure The Isle by Spear Witch, we can see what looks like a series of boxes with a few lines connecting them.

These connections and shapes provide a diagram of the dungeon level but are simplified into an easy-to-digest view. We can see that room 9 connects to 11 and 13, as well as leads to a connection between rooms 3, 1, 8, and 10 with just a glance. We don’t have to worry about how far the players have to walk between those rooms because it ultimately doesn’t matter. If it does matter more than just the GM narrating what the hallways look like, you can take the time to draw out a detailed map, but more than likely… it’s just not needed.

If the abstraction of that example throws you off, keep reading to my example below.

Benefits

Beyond simplifying your dungeon prep, since you don’t have to worry about accounting for every 5-foot square and that hallways line up and flow correctly, you get to the real meat of your dungeon. You already know you want to include a fight with a group of orcs in a large dining hall with plenty of benches and columns to provide an interesting terrain, but now you don’t have to waste time drawing the hallways to get to the feast hall. You simply draw a line to whatever rooms will ultimately connect to the feast hall, and you are good to go.

Page 96 | Neverland, Andrews McMeel Publishing

In addition, you’ve now highlighted to yourself what rooms are actually important in your dungeon. You don’t have to worry about forgetting an encounter, or locating where the stairs are in your dungeon, you have a diagram. Your diagram is well laid out, it’s easier to spot important elements, and it just makes your prep that much faster.

Negatives

Now I’m not going to claim that it’s only benefits for this type of dungeon drawing. It may not be the prettiest thing to throw up on a virtual tabletop. If you show this dungeon map to your players (after you're done with it), it may not hold the same charm and thrill as more traditionally drawn maps, and it lacks the nitty-gritty you might need in your game for rare situations.

Perhaps your players do want to barricade a hallway, its nice to have that already laid out and figured out as a map - but how often do your players really need a hallway or tunnel drawn out for them? Additionally, those are typically very easy to just come up with on the spot and not worry about how it fits into the dungeon as a whole since you aren’t constrained by a bunch of other pre-drawn hallways.

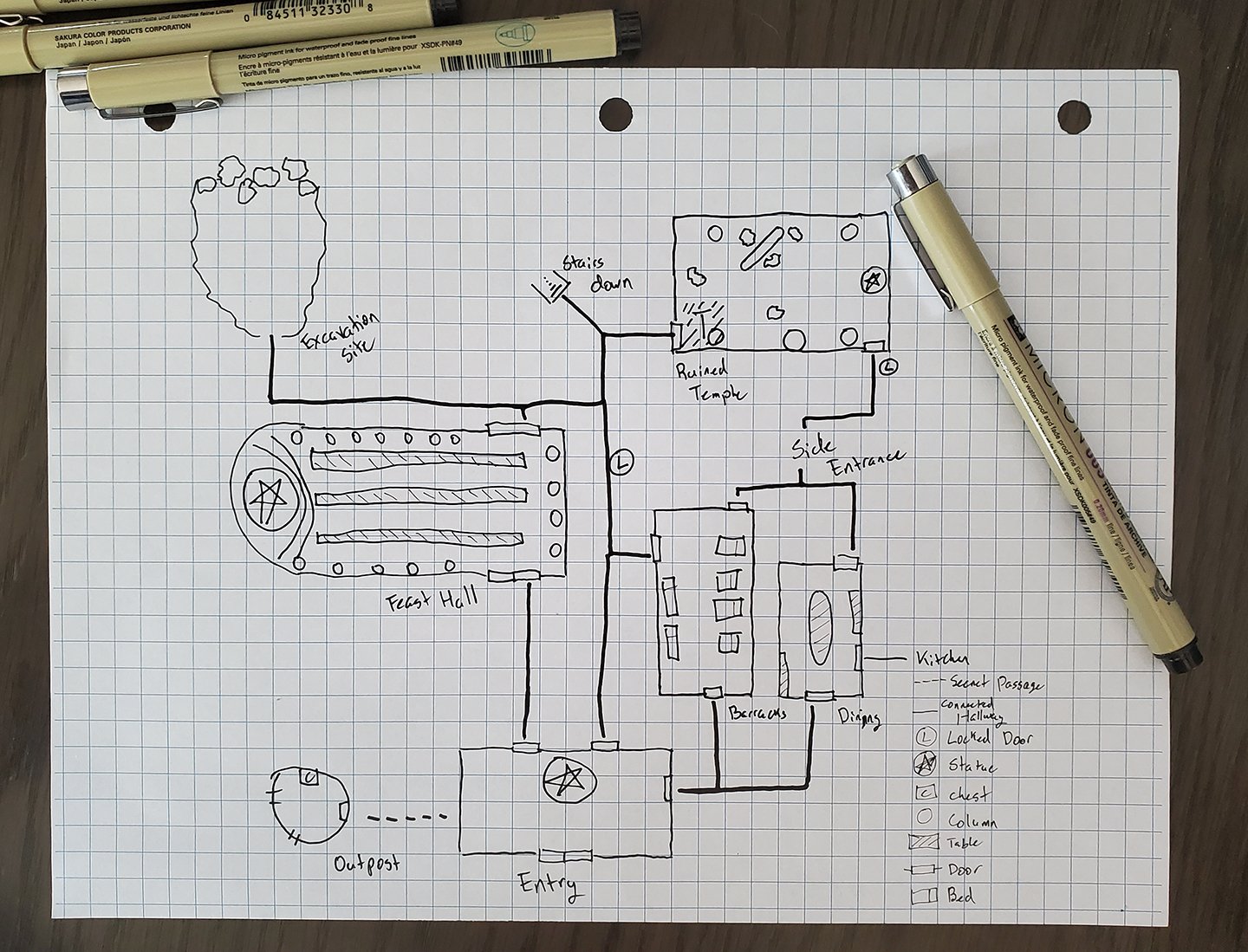

Creating A Dungeon Diagram

To show off how easy it is to create a diagram, complete with some finished rooms and encounters, let’s go ahead and create our own dungeon!

Blank Map, Stephen Bandstra

We are just going to start with a standard piece of grid paper. Unlike the first example I showed you, I actually do want to have a bit more detail in each of my rooms than what their abstractions provide so I’m using graph paper. You can go either way, it all depends on what you want out of your map, how much you want to create before your game, and what you find important to your creative process.

As for the idea of this dungeon, I’m going with an orc stronghold built into the side of a mountain that the orcs are slowly reclaiming after it has been long abandoned. Throughout the structure will be statues of a long-forgotten orc deity or hero.

Entry & Dining Room, Stephen Bandstra

Our first room is the entry with a large statue in the center, along with three doors leading off from there. I already have our first connected hallway leading off to a posh-looking dining room (for the commander and friends), attacked to the kitchen.

You’ll notice, I haven’t drawn out the kitchen because it’s not important for me to have an encounter there. I want an encounter to happen in the dining room with the party finding the chef and servants setting the table for the commander’s meal. If the party wants to go through that door on the left, I’ve gone ahead and just marked it “Kitchen” so I know, but I don’t need to waste any more of my prep time on that because it ultimately won’t matter for me to draw it out. If I need to in the game, I’ll spend the time to do so, but for now, I don’t see it as a major encounter point. It doesn’t get more than a few seconds of thought towards it, and then I get to move on to more important things.

Secret Room & Barracks, Stephen Bandstra

I fooled you! I told you that that entry room only had three doors, but it has four! That secret corridor leads off to an outpost with a few orcs and a chest in there. This way the party can feel particularly smart in locating some treasure I’ve left in the chest (and if they don’t find the secret door, the orcs will come up behind the party and attack… so they better be looking for secret doors!).

In addition, I’ve added a barracks and a few more connecting paths as to how these rooms flow together. Maybe there are rooms in between them, maybe their are corridors. Right now, it doesn’t matter - that’s not part of my prep and if, during the game, I come up with something to put there or my table wants to do something there, then that’s when I can fill in those empty spaces with actual content that will matter to me and my table.

Again, no sense in wasting time on things that won’t come up. Time is valuable.

Feast Hall, Stephen Bandstra

Well, well, well - looks like I get to include that feast hall I mentioned earlier! We can see how it connects with the other rooms, providing the party multiple ways to travel around the dungeon. The key thing to diagrams is that they aren’t there to stop your party from having the freedom to explore as they wish, but rather to make the Game Master’s prep easier (while still providing plenty of options and freedom for players).

Excavation Site, Stairs, & Ruined Temple, Stephen Bandstra

I’ve now added in a key, an excavation site, a set of stairs leading deeper down, a ruined temple, locked corridors, and more to this top level of the dungeon. No commander in sight, but perhaps if you go down the stairs, you’ll find them there…

As you can see from my map, this orc stronghold is probably massive with TONS of rooms to explore, but instead of burning all of my freetime on prepping an orc stronghold map for my table, I spent less than twenty minutes quickly drawing the key areas where I had an encounter idea, a key feature I wanted to highlight, and how all of those rooms connect with each other. We can see locked hallways with a glance, that there is a secret passage, that the players could be clever and go for a side entrance, and more.

This map works just like every other map, you just don’t have to worry about all the things in between the major encounter elements that you WANT to spend time on.

Map It Out

I hope this style of dungeon design works well for you! I find having a stripped-down map to help speed up my prep, remove some of the frustration and indecision I had when drawing maps, and keep me excited to actually run a dungeon. I no longer have to worry about a dozen rooms that don’t really have major encounters in them, instead, I get to focus on the things that matter to me, the story I want to tell, the encounters I want to have, and the things that matter at the table!

Like what we are doing here?

Support us on Patreon!

You’ll get early access to deep dives, our Homebrew Hoard,

monster stat blocks and more!

Follow us on Twitter to keep up to date on everything we talk about!